INTEGRATION of Global Climate Stability Efforts

Arctic Sinkholes

Colossal explosions shake a remote corner of the Siberian tundra, leaving behind massive craters. In Alaska, a huge lake erupts with bubbles of inflammable gas. Scientists are discovering that these mystifying phenomena add up to a ticking time bomb, as long-frozen permafrost melts and releases vast amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. The scope of melting permafrost—which stretches to about a mile below earth’s surface–is equal to about the US and Canada combined. Carbon locked in permafrost is about 1,400 Billion metric tons—a lot! Lakes are formed that release more methane and the process is a positive feed back loop…it cannot be stopped.

Permafrost melting continued: In northern Alaska, there are methane pools 500’ of frozen earth.

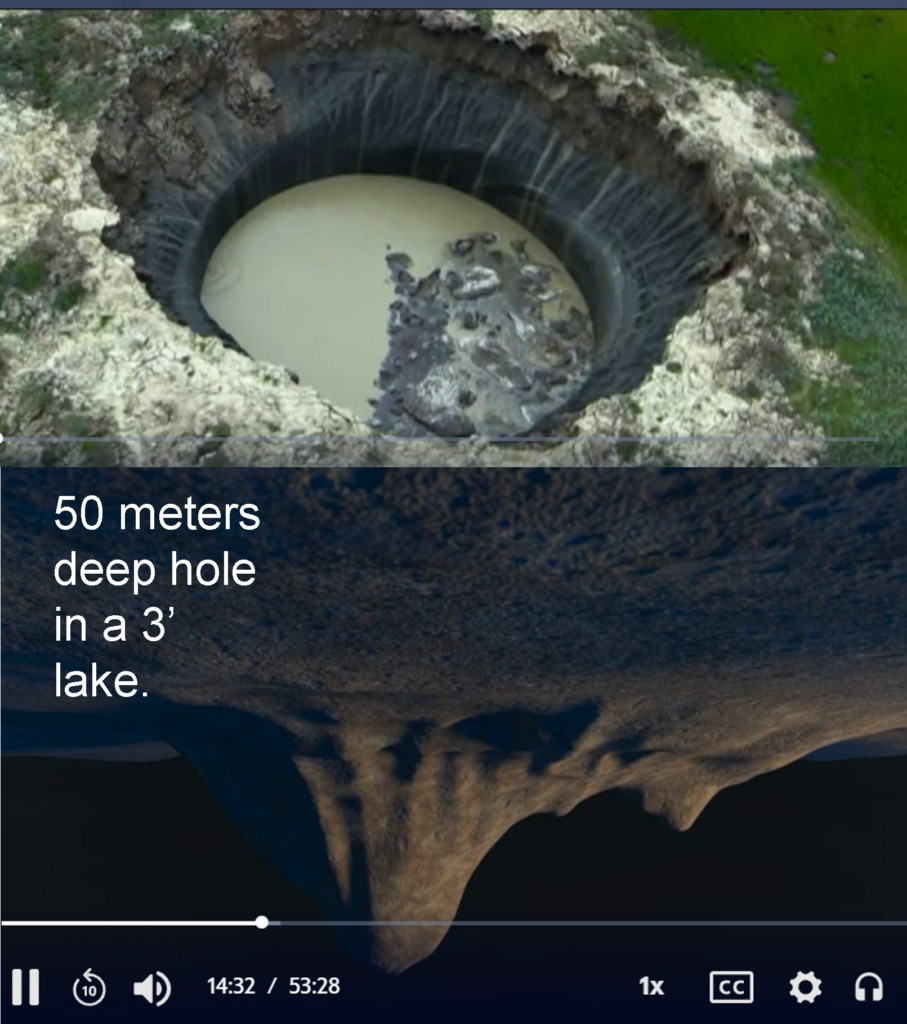

In Siberia, where they found the 50’ sinkhole, the scientists are scanning the permafrost with very low frequency (VLF) equipment. VLF produces an electronic wave as it moves through earth the equipment show the speed at which the wave moves, which notes if the earth is frozen or not. The scan reveals that there is an anomaly. The blue is permafrost and everything else is a thawed chimney from somewhere below 150 meters rising to the surface where we see the rising bubbles. Using VLF, scientists can see 10 times deeper. A warmer, semi-permeable chimney has warmed right through which fossil methane rises to the surface.

There are two sources of methane:

- permafrost release methane when melting;

- as thaw chimneys form within it, they provide an escape route for fossil methane which has been safely trapped for millions of years. Scientists think that there are 1.3 trillion tons of methane stored beneath the arctic. That’s at least 250 times the methane that is in the earth’s atmosphere today. Seventy sites have been found to have methane seeps. There’s a huge amount of methane inside and under permafrost. If there are chimneys venting the methane in these sites, they are not included in climate models.

How fast and how much fossil methane can come out we don’t know, but this will make human effective action even more important. How a human made feed-back cycle actually works: Scientists currently don’t know how fast these feedback loops could occur or what it would look like. There’s one place where a human-made permaculture feedback cycle occurred. How a human made feed-back cycle actually works: Scientists currently don’t know how fast these feedback loops could occur or what it would look like. There’s one place where a human-made permaculture feedback cycle occurred. In NE Siberia in the Chersky Mountains in 1960s in Vatakayka a stretch of forest was cleared to make a road. Stripped of its tree cover the permafrost was exposed to the warming sun.

The ground sank pulling down trees as it thawed—a positive feed-back cycle. How a human made feed-back cycle actually works: Scientists currently don’t know how fast these feedback loops could occur or what it would look like. There’s one place where a human-made permaculture feedback cycle occurred.

In NE Siberia in the Chersky Mountain Range in the Transbaikalia Region in 1960s , the people of Yakutiva cleared a stretch of forest to make a road. Stripped of its tree cover the permafrost was exposed to the warming sun. The ground sank pulling down trees as it thawed—a positive feed-back cycle. The depression is 300’ deep and ½ mile wide—and it’s growing. Scientists call it a mega-slump. Every summer it gets bigger. A small human action created a mega feed-back cycle. What would a feed-back cycle mean for the entire permafrost region—when or whether it becomes irreversible. This is a tipping point—the point of no return. Two tipping points are being studied by climate scientists: arctic sea ice and deforestation in the Amazon. Some scientists believe that some aspects of the thaw are irreversible.

Romanowski, who has been studying the permafrost for decades near Utkiyawik in northern Alaska. He attests that the lakes formed by melting permafrost has past the point of no return. “It took tens of thousands of years to put that ice into the ground. It used to be a flat area. Then ice melts and the surface subsides. It would take tens of thousands of years to freeze it again.” That, for humans, is definitly an irreversible process. The roads outside Utkiyawik are subsiding. In the town, the houses are subsiding. Nelson thinks the housing needs to be torn down and rebuilt with better pilings on firmer ground. In another town, Griffin Hagel CEO Regional Housing Authority, has a more radical plan for sinking homes: Portable, adjustable, sled-based homes as opposed to pilings. Steel chains from a caterpillar would be attached to steel stub-outs with holes built into the infrastructure of the home and the home would be towed across the snow (ski across) in the wintertime to an area where the permafrost is firmer. Hagel deals with “the largest municipality based on land area. We provide affordable housing in eight villages across an area the size of Minnesota—only without any roads”.

None of the houses have been pulled away yet. Several communities are at risk of relocation, so having the ski-mounts give the people the advantage of having the mobility they need to move structures, when necessary. Indigenous people have called these places home for thousands of years. There’s a long tradition of innovation. As inhabitants adapt to their changing world, scientists strive to build a better picture of our climate future. The sink holes are one sign of unprecedented changes “placing indigenous people with deep ties to the land at risk. E.g. the whaling communities have been whaling for over 4,000 years. We’ve adapted time and time again. Today, we may no longer be able to do it by ourselves”, indigenous spokesperson. The big thaw is not just a regional problem, what’s happening in the arctic impacts everyone else on earth. Arctic greenhouse gases will intensify future global warming. How quickly, is difficult to predict. We don’t know as positive feedback cycles could accelerate beyond human control making our choices today even more urgent. Because it is very difficult to take over the natural systems, it is even more important for us to lower our emissions. The craters in the permafrost are important indicators that things are changing and the arctic is melting, the arctic is thawing and the future of the arctic is a very different place than it was several decades ago.