Introduction

Fertile farmland is one of our most precious natural resources—a complete symbiotic ecosystem that feeds every human on the planet. Healthy soil teems with billions of living microorganisms. This survival of humankind on this earth has been measured by our ability to grow a deep personal relationship with our farmland—this topsoil, this tilth—and protect, nurture, and preserve this complex and fragile origin that forms every aspect of physical bodies.

Fertile farmland is one of our most precious natural resources—a complete symbiotic ecosystem that feeds every human on the planet. Healthy soil teems with billions of living microorganisms. This survival of humankind on this earth has been measured by our ability to grow a deep personal relationship with our farmland—this topsoil, this tilth—and protect, nurture, and preserve this complex and fragile origin that forms every aspect of physical bodies.

Radical shifts in American agriculture in the last six decades have disconnected most Americans from the source of our food—the soil, water, and all the living organisms. We have chosen, instead to grow an economy based on profit, not health, and turned basic food sustenance into a business, not a right. We witness every day how industrial food products have obliterated our primal connection to soil.

We can regain this critical connection by focusing on food, farming, and financial infrastructure and promoting one model that can be replicated in any community in America. Using programmatic advocacy and investment practices, we commit to high quality food and farmland, as well as improved health and well-being of surrounding communities.

This new initiative is called the Local Foodshed Resilience Program (LFRP). A community can utilize the LFRP to develop the philosophy, infrastructure capacity, and all other practices needed to sustain a healthy food system.

The first step toward Local Foodshed Resilience is to assess the community’s foodshed. A foodshed is not limited to geographic boundaries. The Lexicon of Food organization describes it in this way:

“While natural resources and economic infrastructure provide a template, a foodshed doesn’t really exist until a collective vision is called for and cast — whether by engaged citizens, concerned consumers, entrepreneurs, or policymakers. Ultimately, a prospering and healthy foodshed is [defined] by the periphery of a community’s ability to create positive change for the common good….and becomes a collaborative vision and a shared reality.”

A community grows its foodshed resilience in alignment with its soil, weather, demographics, and the cultures as a community, making each foodshed unique. Understanding the place called “home” is central to the process. Consider these key questions:

- What is the character of our soil, weather patterns, demographics, and cultures in this place we call home?

- What philosophy maximizes the sustainability of the farmland, watershed, and living beings as well as the fulfillment of all the members of our community?

- How can every person in the community participate in the education, production, distribution, preparation, and consumption of locally-grown food?

- How can funds “held-in-common” and the means of education, production, distribution, preparation, and consumption of local food enable equal access to healthy food for all community members—regardless of race, gender, economic status—to catalyze the creation of a food democracy?

The answers become the guide into the socio-ecosystem of the LFRP, which evolves by mutual agreement among community members.

Shift in U.S. Agriculture

Over the last 30 or so years, agriculture in this country has been driven by profit and, thus, land is more intensively farmed. Tilling and the pesticide and fertilizer load have broken the mycelia web and biodegraded the deep water capture, thus creating topsoil runoff. Agronomists and bio-resilient farmers, such as John Jeavons raise the issue of increased global soil loss. Jeavons and others are cautioning that although this statistic varies around the globe, there is a call that we now have only “28 years of soil left”. Rebuilding our tilth is now a global priority. How could this have happened? Yields are driven higher with more capital and labor, rather than the more traditional

systemic agriculture that is grounded in the land’s organic carrying capacity. Natural systems include companion planting, crop rotation, and inputs from animals, all strategies which increase both the fertility and civility of the enterprise, but are rarely used in conventional farming today.

Our farmland has been transformed. The relationships among our farms, our food, and our communities have gradually disintegrated. Now genetically modified corn and soy beans comprise over 50% of all U.S. farmland acres. The vast majority of corn is grown for fuel and livestock feed, and the inputs to GMO-based, as well as conventional farming practices, have taken its toll on the health of the environment, humans, and animals.

The detrimental impacts of commodity farming and concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) are rippling

across the most fertile farmland in the country and outgassing methane into the atmosphere—at 20 times the impact of C02. Livestock are filled with hormones, antibiotics, and growth-promotants (pharmaceuticals used to accelerate animal growth). Processed food containing high levels of sugar, salt, and fat continues to destroy the health of people of all ages and backgrounds, and is linked to the dramatic rise in obesity, diabetes, heart disease, strokes, and other ailments.

Another choice is available since each community has a capacity to create a healthy food system, and the LFRP strives to elevate this process.

Key Elements of LFRP

Once a community has identified its foodshed, it must begin identifying the five core components of the LFRP which form the basis for a resilient foodshed community:

- Philosophy: based on integrated inquiry, shared fulfillment, and the growth of a learning-community

- Enterprise: support enterprises to maximize the community’s food production available for all its members and for trade

- Members: enable community residents to reach their full potential (self-actualization)

- Equity: create food and gender-based equality and democracy

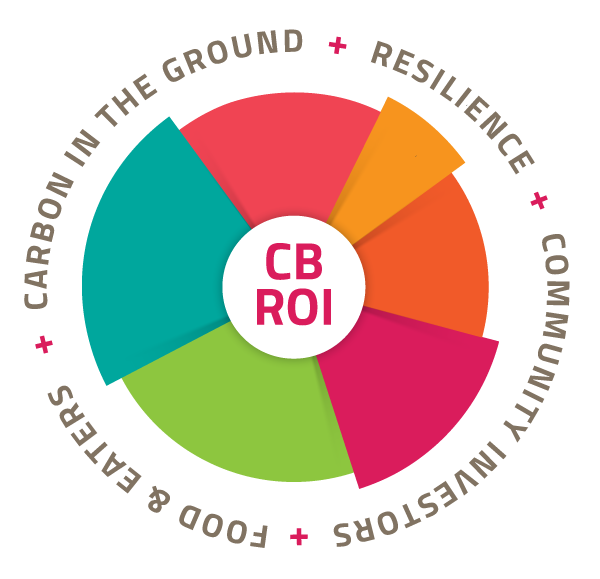

- Finance: grow community assets-in-common and support LFRP by using the Community Benefit Return on Investment (ROI) metric

Within communities, how we acquire food is vitally important: each transaction, or exchange of goods, would produce something valued by the community-at-large, the socio-financial permaculture. The community’s food exchange would environmentally, socially, and financially reflect—or biomimic– the inter-dependent processes the microbes in soil employ to become tilth. It shows how the whole community is valued, allowing it to grow and sustain itself—regenerate—toward a healthy and resilient future.

Within the LFRP Design

The LFRP includes another unique perspective, drawn from a systems-based approach based on a biomimicry. The end result is enhanced efficiency, often leading to reduced energy use, less waste, and greater sustainability.

For example, an LFRP community first functions as the “pupa” or cocoon phase of a butterfly. It is intra-dependent, and focuses on activities to help learn who “we” are, and what “we” know about food, farming, and finance. Community members need to learn how to collaborate effectively for the greater health, fulfillment, and sustainability of the community. LFRP has been weaving together a set of capacities—known at this time as the Community Communications Tool Suite. (Described later) After the foodshed community evolves to encompass the five core components and reaches other milestones (to be discussed later), the community enters the “emergent” phase, where members share their learnings, best practices, and resources with other locales, so these communities will eventually be inter-dependent and can co-evolve.

One important infrastructure enterprise is the food hub, an entity that aggregates, distributes, and markets locally produced food from small-to-mid-sized farmers, ranchers, and fisher-people. They support the local farming economy while providing community members with fresh, sustainably-grown food from nearby sources that practice healthy environmental stewardship and animal husbandry. Since smaller farms lack the volume to compete with massive distribution networks, a facility dedicated to local farmers and local food distribution is a keystone component of a resilient foodshed.

Another key infrastructure enterprise, sometimes located in the same facility as the food hub described above, processes and packs fresh food—preserved by drying, canning, jamming, fermenting, and freezing for consumption during non-harvest seasons. Thus, all the value produced by the land and from the efforts of community members will be fully integrated into the foodshed—no wasted land, no wasted food, yet another infrastructure component upon which community members can work together, grow their community foodshed capacity, negotiate and experience food equity and reach their potential while contributing to the whole.

Fairfield, Iowa & the Local Foodshed Resilience Program

Amid the vast expanses of corn and soybeans, in the southeastern corner of Iowa is Fairfield, a town of approximately 10,000 people experienced a wave of new folks 42 years ago. Many towns have experienced people moving into town with the resulting changes in community character, demographics and culture. 1974, the Maharishi International University, now Maharishi University of Management, moved onto Parson’s College campus and a 42 year long dialogue between those drawn to and practicing Transcendental Meditation and the local, mostly Presbyterian, community began. The fundamental change Fairfield has undergone is now maturing into a collaboration around health and wellness and living full lives based on healthy food for all.

Fairfield has begun to inquire about the Local Foodshed Resilience Program—a dynamic work-in-progress, building on explorations into sustainability practices. Fairfield is considering how they might serve as the proof of concept model, to seek a way to enable other communities to take part in their own unique learning journey towards sustainability. One goal is that LFRP templates created, adapted, and expanded by the Fairfield community it is leading the way to enable other communities to take part in their own unique learning journey towards sustainability. LFRP templates created, adapted, and expended by the Fairfield community—vetted and supported by collaborators, will be available for use by other communities to adapt to their own unique circumstances.

Fairfield is growing a commitment to create a sustainable and healthy future for all of its community members. A diverse group of stakeholders developed a strategic plan for 2009-2020 called the Go Green Program, which started them down a path of sustainability for three key areas: community and culture, economic development, and land-use, building, and transportation design. The plan includes a vision “to support a prosperous local farm economy to meet consumer needs and tastes.” In alliance with the LFRP, Fairfield will deepen its community’s commitment to sustainability.

Fairfield’s stakeholders see their community as an education center for local, organic, no-till food production and processing. Fairfield is the county seat of Jefferson County, which had over $1.1 million of organic food product sales from its farmland according to the 2012 USDA census; the entire state of Iowa produced organic food worth over $57 million in the same year.

Context is important however, since Fairfield is an oasis amid millions of acres dedicated to the industrialized food complex. Iowa ranks #1 in the U.S. for both the production of corn and soybeans—more than 90 percent of which are genetically modified. The value of the production of those two crops in Iowa was $8.7 billion and $4.8 billion respectively for 2012.

Regarding livestock, Iowa holds the top ranking spot for in hog production in 2012 with over $6.7 billion in revenue. Incredibly, as of December 2015 over 20 million live hogs were inventoried in Concentrated (or Confined) Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) that house many thousands of hogs in a single building in documented deplorable conditions that risk degradation of the water, soil, and air quality.

Infrastructure Enterprise: SE Iowa Food Hub

In keeping with the stakeholders’ long-term vision of sustainability, the Southeast Iowa Food Hub opened in Fairfield in late 2014. As of this writing the SE Iowa Food Hub sources food from 35+ farms in 13 counties surrounding Fairfield. It builds capacity for the organic farms by centralizing food aggregation and distribution, while growing the marketing of local food in the region. Its success to date includes distributing organically-grown food to larger institutions such as the Jefferson County Hospital and Maharishi University.

The SE Iowa Food Hub runs on a largely volunteer work force and is based on the following values, ones clearly in sync with the LFRP:

- Access to affordable, healthy food is vital to a healthy, sustainable community.

- Relationships should be nurtured between local producers and local consumers.

- Extending growing seasons and eating seasonally will build capacity for year-round availability of local production for local consumption.

- Farmers and consumers share a common commitment to sustainability, and given the opportunity, will work together to create a more sustainable local food system.

- Sustainable organizations are built upon a foundation of personal integrity and mutual trust, and shared social and ethical values are essential in sustaining collaborative organizations.

- Local food systems create and multiply wealth for our local economy.

The experiences of the SE Iowa Food Hub will help inform

communities investigating a future as a foodshed-resilient,

sustainable community.

Fairfield, Iowa and Proof of Concept Community

Fairfield’s community members’ inquiry into their food system formally began with the creation of Fairfield’s 2011 Go Green Program, and again with their submission in the Biomimicry Institute’s 2015 Global Design Challenge in Food Systems. The town of Fairfield is again carrying that ball further down the field and actively inviting and engaging all Fairfield community members through a LFRP Proof of Concept phase. The leadership team is actively “opening up the community tent” towards the goal of adopting the LFRP as the Proof of Concept Community.

Pupa Stage

Resident decision-makers in Fairfield, or any locale, have the opportunity to grow a community-wide knowledge base using the Goodfoodweb.com, one component of the Community Communication Tool Suite provided by LFRP. GoodFoodWeb.com enables each foodshed community to draw on each other and allies beyond their community to: aggregate their food, farming and finance knowledge; gather, evaluate, and track data; find experts; get help—facilitation, training, certificate courses–and analyze information about the community’s food resiliency. As a community chooses to investigate the LFRP, each will log onto the site and populate its own data and information at GoodFoodWeb.com. Using the biomimicry analogy, in the “pupa” or “cocoon” phase, self-designated community members access the GoodFoodWeb.com on the LFRP web site, each community logs on to the LFRP website, receives a unique password-protected area. The site prompts users with key questions about their community that enables them to grow to know: What is this place called home? Who lives here? And how can we grow shared knowledge to create health and foodshed resilience?

To answer these questions, the Fairfield community assesses its natural, municipal, and human capacities. This requires a deep dive into weather patterns; agronomy of soils; demographics of residents; broadband availability; health facility access; access to affordable farmland, tax base for municipal services including crime-related services; percentage of residents who have access to healthy food and those who purchase such food; cultures within the community; impact of the cultures on younger community members as well as enabling their young people to grow their capacities for leadership roles. A result of thinking deeply about community imbalances, Fairfield, IA identified a current issue to address—namely, that 19% of their community population is food insecure. Therefore, the community seeks a strategy to address this issue.

The LFRP site offers drop-down menus and built-in feedback practices for the educational opportunities within LFRP such as certificate courses on soil health, watershed management, and agro-ecological farming. Another menu will focus on the self-actualization food democracy curriculum which will include creative facilitation, team building exercises, and training around issues related to marginalized community members created to lift themselves up (defined for each locale). Site subsections such as “Galleries of Talent” and “Galleries of Experience” are available to support communities in addressing social challenges and to develop environmental, financial, and governance business strategies.

The community assesses its capacity on three levels: general, peer-to-peer, and professional that are labeled throughout the Community Communications Tool Suite. The suite is comprised of the GoodFoodWeb.com; a prospective alliance between MESA’s Agro-ecology curriculum and certificate courses and Maharishi School of Management’s curriculum and certificate courses; and e-Harvest HUB’s tools that enables farmers to label their produce’s farm of origin thus complying with the source tracking requirement for produce as set forth by national law.

Emergent Stage

Once a community has completed a thorough foodshed resilience assessment and the key infrastructure components for their community are “live,” the LFRP’s “emergent” or inter-community phase begins. Through an integrated network foodshed resilient communities can co-evolve through a variety of forums, group processes, and other innovative means of communication that enable all communities participating in the LFRP to share best practices and other wisdom.

What kind of mindset and landscape are necessary to sustain a resilient foodshed in Fairfield? To enroll a broad base of community members, Fairfield will present a Fairfest 2016—Local Food Summit–in collaboration with their annual Labor Day Music Festival.

Test drive LSRP web site following this article:

- Experience a graphic overview of the LFRP

- Sign up on the LFRP site

- Place a sample food and farming infrastructure components on a generic LFRP “landscape map.”

Interested community members can “log on” and kick the tires of this very alpha web site, return at any time and begin to place live! foodshed infrastructure enterprises on their own foodshed map.

Start off what can become a sample of your community’s “landscape map” that can be developed on your community site on the LFRP website over time with infrastructure components of a thriving foodshed. Community web managers (up to 3) can sign on and upload a community map right away. Your own community map will now appear ready for you to drag and drop food, farming, and finance infrastructure component glyphs onto your map. Your progress will readily communicate to your fellow community members “Hey! We’re moving right along here!”

The Local Foodshed Resilience Program invited some enterprises among us to collaborate in making the potential accessible, clear, and actionable. Through these web-based tools we are inviting communities to collect data and learn about other members of our community—and know OUR places called “home.” Community members populate their own foodshed map with both the mindset and the enterprises that drive a resilient community. While most are physical capacities and resources, virtual ones such as a shared philosophy, education activities, and sustainable practices are included as well. Thus, a community foodshed “becomes a collaborative vision and a shared reality.”

Each and every parameter of the LFRP’s organic framework can be customized to address a community’s unique circumstances. These frameworks enable any community to embrace their capacities and resources and grow them forward. When a community decides they are sustainable, they enter Phase 2 of the LFRP, Emergence. In Phase 2, communities can join a network of communities with their systems-based approach to food resiliency. When a foodshed is resilient, it is strong enough to retain its form and function amid a myriad of external forces, including the detrimental effects of the industrialized food complex which floods processed and unhealthy food—and all related advertising–into the marketplace.

Diving Deeper into LFRP’s Philosophy?

The LFRP is based on the premise that foodsheds are living landscapes with vibrant, biodiverse populations which need attention and many resources to thrive. In 2015, Fairfield and supportive team members from greater Iowa, New York and California, submitted a LFRP design phase to the Biomimicry Global Design Challenge in Food Systems. In that submission, the six team members put forward six fundamental perspectives necessary to select systemic projects that drive foodshed resilience in their community and used those criteria for their program selection processes.

These six LFRP perspectives are filters hard-wired into all LFSR local foodshed evaluations: presence/awareness; bio-resilience; food, farming, and finance infrastructure design; role of culture; regenerative value exchange; and food democracy. Each function is led by a community member with talent and enthusiasm for that particular perspective of the LFRP. For the 2015 Biomimicry Global Design Challenge in Food Systems, we used the honey bee metaphor for two fundamental aspects of the LFRP: 1) since a honey bee hive cell constitutes a hexagon, a fundamental building block of life, in addition to being the basis of honey bee place-based resiliency, each of the six team members represented one side of a hexagonal cell focused on these six perspectives.

This imbues the LFRP with the following capacities:

- Presence/awareness: The community recognizes and promotes cultural qualities to support integrated whole systems of health and well-being. The way of being that enables all community members is live into the presence of a “learning community.”

- Bio-resilience: An integrated local foodshed system—based on biodynamic practices—enhances nutrition for all while enabling the respect, and the financial success, of both local rural and urban farmers.

- Infrastructure design: The infrastructure for food, farms, and financial systems is designed to ensure foodshed resiliency.

- Role of Culture: Draw from our many ancestral and contemporary models of success in creating foodshed resilience.

- Regenerative value exchange: In support of these efforts, a financial and transactional system must be in place to enhance–not detract from–the local food system. Community Benefit ROI serves as a solid next step in this process.

- Food Democracy: Each foodshed enables and grows all members so each has a path to his or her highest potential. All community members are engaged in the education, production, distribution, preparation, and consumption of the food.

When a honey bee hive is successful and produces a new queen, the old queen takes about half of the hive and scouts find a new hive. Scouts use a process, not uncommon in many insect species, called quorum sensing. Quorum sensing does not require 100% consensus, but does require that of the scouts who have selected sites that are still under consideration make a final decision. Biomimicing this selection strategy enables a quorum in a community to consider whether or not to investigate the LFRP or not. Further, when a community logs on to the LFRP website, it receives a dedicated number and can step in and out of their password protected LFRP site anytime. This enables each community to proceed with their inquiry at their own pace. Thus, the LFRP ensures any community will benefit from undertaking the inquiry and, with due diligence, realizing the health and vitality benefits of an active food democracy growing foodshed resiliency.

The LFRP bio-dynamic, no till, permaculture framework helps communities chart their own course to foodshed resiliency. The healthy food we eat comes from the vigilant stewardship and agro-ecological practices used on farmland, free of the conventional pesticides and bio-engineered systems which degrade our health and our fertile soil. Under discussion among agronomists, bio-resilient farmers and indigenous permaculturalists is a sobering statistic that there are only 28 more years of soil on this planet. We must use practices that build the living systems that give us life and health.

The LFRP bio-dynamic, no till, permaculture framework helps communities chart their own course to foodshed resiliency. The healthy food we eat comes from the vigilant stewardship and agro-ecological practices used on farmland, free of the conventional pesticides and bio-engineered systems which degrade our health and our fertile soil. Under discussion among agronomists, bio-resilient farmers and indigenous permaculturalists is a sobering statistic that there are only 28 more years of soil on this planet. We must use practices that build the living systems that give us life and health.

The food from a sustainable and resilient foodshed is transformational: it is the result of what is sown and reaped from healthy, fertile farmland, as well as the efforts of those community members who are integral to the biome. Each member of this community is valued—whatever gender, age, or income–and is given opportunities to learn, grow, and be fulfilled.

Our communities, our bodies, and our farmland exist within an intricate, delicate web—a local foodshed—which when nurtured and properly tended, can become resilient and ultimately produce health and vitality for all living things.

Invitation to All Communities

The LFRP is an invitation to all communities: it is an organic systemic solution to improve the health of its members and the consequent stewardship of their farmland, creating an ecosystem for a sustainable–and resilient—foodshed.

Again, geographical boundaries alone don’t define a foodshed. It is also the reach of the collective vision and actions of its community members: what a group of like-minded individuals can impact through its policies, volunteerism, shared-learnings, programs and enterprises, along with the community members’ participation in the education, production, distribution, preparation and consumption of its locally-grown food. The cumulative actions of community members are what so exquisitely delineates the fluid borders of a foodshed: the LFRP reflects this flexibility in its foundational framework.

The Future: Our Health, Our Farmland, and Our Communities

Now is the time to STAND-UP to the industrial food system and CHOOSE a better and more healthful way to live. We cannot keep moving in the wrong direction—we lose our health, our soil, our capacity to grow food, and our community member’s and community’s assets, which belong to every member of the local foodshed. Sustaining this “wrong direction” depletes our land and our bodies while severing the community’s primal connection to its food. We must question–and DISRUPT–the status-quo of industrialized food systems.